Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim wrote in his 1977 classic, The Uses of Enchantment, that fairy tales and other fantasy stories provide a safe stage where young people can rehearse life’s big events, playing out their dreams and nightmares. Story-tale heroes are like avatars kids can use or discard without consequences. But what about villains? What is it that makes a villain so irresistible to kids? What do we mean by a ‘good’ villain?

What role do villains play for us? What kid–or adult, for that matter–can resist a good villain in a book, film or theatre performance? How bland would our stories be without the foreboding and danger provided by a good villain?

A ‘good villain’ is definitely not a good person. Young readers need to see heroes overcome villains. Good must triumph over evil if life is not to be unbearably frightening. And a hero without a villain has no challenge.

The element of surprise in any story is exciting, and a good story-teller’s villain should be unpredictable. We should not know what he or she will do next. As kids know better than anyone, no one can be good all the time.

Villains give kids someone to relate to when they have been cruel, told lies, or hurt others. Villains give us models for our dark moments. A good villain sometimes has a tragic backstory that explains–and to a degree, excuses–their villainy. Without villains, it is hard to learn what it is to feel remorse, and to grow from it.

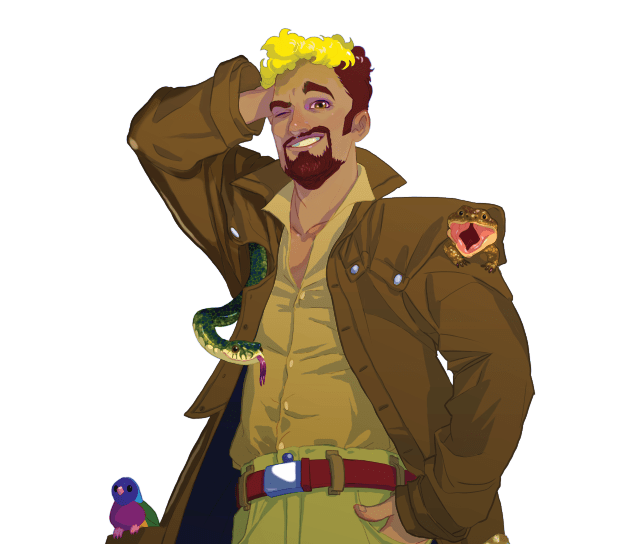

The Great Brassmonkey Bay Jewel Robbery introduces three villains to the Magic Island Gang series. The first we meet is Sammy Snatch, a heartless smuggler of endangered animals. Clad in a long coat with pockets that are stuffed with his tiny prey, how can Sammy be anything but despicable? He’s a rough fellow. When Sammy gloats over his successes, we imagine him at home after a long day of trapping and poaching, sitting in his chair with a groan, and bending over, we think, to pull off his muddy boots.

Until he pulls off his wooden leg and tips out a little marsupial mouse!

Immediately, we are taken aback. The unshaven Sammy is admittedly a good-looking rogue. His wooden leg adds mystery, the possibility of tragedy, and even a touch of rock-star glamour to the fellow. What is Sammy’s back story, we cannot help but wonder?

Time after time, in the story, Sammy commits unconscionable crimes. But despite this, we never quite turn our backs on him.

Instead, we forgive him when he traps and sells endangered animals to the story’s second villain, the greedy Zoo Director Caspar Hustle. We forgive him when he can’t help but flirt with the third villain, Scarlet Swindle.

We forgive Sammy when he hangs around Brassmonkey Bay, living off his ill-gotten gains, too lazy to do his job.

When he cons Director Hustle by selling Pilfer Possum as an endangered animal, we forgive him again.

We even forgive him when he tracks down the Gang, aiding and abetting a plot to bring them down.

Why?

Sammy is quirky. Dangerous. But he is also funny. Sammy is handsome enough to be the boyfriend even good girls wish they had had, if only for a short spell. In fact, Sammy is such an appealing villain, there are times in the book when he threatens to hijack our sympathy! At the end of The Great Brassmonkey Bay Jewel Robbery, Sammy gets a serious ‘time out’ to think about his crimes.

Does it work?

Either he has to redeem himself sufficiently to merit our readers’ sympathy or he has to continue to behave so appallingly, readers will stop forgiving him for his charm and good looks and attend to their own job of looking after the greater good of Sammy’s endangered victims.

Read The Great Brassmonkey Bay Jewel Robbery to find out.

Do you agree that Sammy is no exception to Bettelheim’s theory? That he offers us lessons in moral dilemmas, a caution against falling in love with the wrong guy, against making self-serving mistakes, against being tempted to make choices we regret?

Listen to Sammy’s signature song, ‘Smugglers’ Jig’ above for clues.

Then watch out for the ‘Artful Gluffster’ post about another Brassmonkey Bay villain–Scarlet Swindle. What does she have in common with Sammy Snatch? And what do Scarlet and Sammy teach us about what makes a really satisfying villain?